Read our 2023 annual report

Knowledge Hub

Agriculture plays a large role in the fight against both world hunger and global poverty.

An increasingly erratic climate, difficulties transporting water for irrigation, and the displacement of farming families by conflict are just some of the challenges facing local food systems. But addressing these issues could mean major gains in development. Here’s why.

The link between agriculture and hunger

Agriculture is how the majority of low-income families earn their livelihoods. Globally, 65% of low-income working adults rely on farming both for their income and meals, and the industry accounts for one third of the global GDP. In rural areas, particularly in the Global South, these numbers are even higher.

Agriculture and poverty

This means that there’s an overlap between agriculture, climate change and poverty. The International Fund for Agricultural Development estimates that approximately 83.5% of global poverty is centred in rural communities, which are less likely to have adequate infrastructure, educational opportunities, essential resources, and other key services (such as healthcare and social safety nets).

This is especially true in sub-Saharan Africa (basically every country on the continent except Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, and Egypt), where over 60% of the population are smallholder farmers. According to IFAD, this area’s poverty rate (41%) is also more than three times the global average (just under 13%).

These two figures aren’t coincidental. Some of the countries that rely most on agriculture are also those countries hit hardest by climate change. In the case of Africa, many countries have also faced crop losses due to violence and conflict, El Niño and La Niña-related events, and the desert locust crisis of 2019-22.

Agriculture and hunger

The poorest people in these communities have the fewest resources to respond to shocks as they happen. They are also at a higher risk for these emergencies based on both the area of the world they live in, and the fact that they live in rural communities.

All of this creates a perfect storm for people who rely on agriculture to also experience some of the highest rates of hunger. Relying on the land for both their living and food means that a bad harvest not only leaves less on the table, but also gives them less income to purchase other staples at the market. In many cases, we can see several causes of hunger and causes of poverty interlock to form a cycle that’s hard — if not impossible — to break for those trapped inside of it.

We won’t end world hunger until we address the needs of smallholder farmers

The solution is clear: In order to end world hunger (and poverty), we must focus on the needs of smallholder farmers and rural communities. This includes focusing on sub-Saharan Africa, as well as South and East Asia, Latin America, and the Caribbean, where poverty rates are among the highest and many residents depend on the land. Approximately 75% of people going hungry today live in these areas.

This has been true for some time. “Current development efforts grossly and increasingly neglect agricultural and rural people,” said Dr. Michael Lipton (Director of the Poverty Research Unit at England’s Sussex University) in 2001.

In the last few decades, investments have gone from supporting small rural farmers into larger, international agricultural industries. But over-relying on food imports from higher-income nations (such as the United States) has also hurt people in the world’s hungriest countries. “The majority of poor and hungry people are small-scale farmers. They are in fact members of the private sector, albeit the weakest. And some corporate investments in agriculture can hurt them,” said John Coonrod, EVP of the Hunger Project, in 2018. “The world has over-invested in low-nutrition staple crops, driving up the relative price of nutrition rich-foods. Empty calories is the food system of the poor.”

It doesn’t have to be like this. The World Bank estimates that, compared to other sectors, investing in agriculture is two to four times more effective at raising incomes among the world’s poorest compared to other sectors.

How can agriculture help solve world hunger?

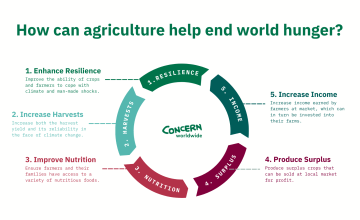

So how can we use agriculture to successfully and sustainably end world hunger? There are five key steps that work together.

1. Enhance agricultural resilience

Our first step is to increase the resilience of farmlands and pastures, particularly those affected by climate change. Climate Smart Agriculture is a set of farming methods designed to increase the resilience and productivity of land affected by climate change. CSA increases food security for farmers and their families. It also means farmers are more prepared to handle both the current and future effects of climate change.

2. Increase harvest yield and reliability

Building resilience into smallholder farmers’ practices means that we not only increase the yield of their crops, but also the reliability of these harvests (despite what nature may throw their way). In Ethiopia, for example, one hectare of potatoes makes 10 times the price of 1 hectare of barley.

“There’s a big difference for my family. With this same field I used to harvest one bag of maize —now I harvest 8 bags.”

3. Improve access to a variety of nutritious foods

Sometimes people have enough food, but it doesn’t provide enough nutrients. Maize, for instance, is a staple crop in Africa (despite not being native to the continent). It’s hard on the land, and while it can be filling, it’s not very nutritious. It’s no coincidence that the prevalence of chronic child malnutrition often intersects with extreme poverty and heavy reliance on a single crop like maize.

We therefore have to increase the diversity of crops — another principle of Climate Smart Agriculture as it helps the soil, and also helps families get the full range of vitamins and minerals they need each day.

4. Produce a surplus of crops for the market

While many rural families are subsistence farmers — meaning that they eat what they grow — there is also enough potential in even a small plot of land to produce surplus crops that they can then sell and trade at local markets.

5. Increase income

With greater yields of better and more diverse foods, people are able to increase their profit, investing some of that back into further growing family farms, buying more land, more or better farming supplies, joining Village Savings and Loans Associations, purchasing supplies to help their harvests last longer and during periods of scarcity, or investing in other income-generating activities to diversify their income sources. As they build more resilience into their land and livelihoods, farmers can more sustainably break the cycles of hunger and poverty.

Home-grown solutions to hunger need support at the national and international level

All of this seems like a good deal and makes a lot of sense when laid out. However, fighting hunger with agriculture does require some larger investments.

First, we need to accept that smallholder and local farmers need to be prioritised as key to solving hunger where it is most keenly felt. Foreign assistance and corporate investments need to be focused locally, rather than relying on international agricultural giants to feed the world.

In some cases, especially in Africa, there is a lot of land that is appropriate for farming, but it hasn’t been touched — often due to instability and conflict. Meanwhile, millions of people are using small plots of land and innovations like home gardens to grow food while living in protracted displacement.

Rural areas are also less likely to have the infrastructure needed for local food systems to survive and thrive. It’s not enough to give farmers the training, tools, and individual resources they need to be successful. We also need to invest in building roads, creating clean water sources, and other initiatives that will serve communities.

Finally, there are policy changes that are holding more than half of the world’s farmers back. In some regions, including southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, women make up more than 60% of the agricultural workforce. Yet they are often prohibited from owning land or getting the same resources and supplies as their male counterparts.

How Concern is fighting hunger with agriculture

The majority of people Concern works with are involved in some way with farming and food production. In countries like Malawi and Afghanistan, it’s essentially everyone.

Many of these communities are also on the frontlines of climate change. We work with rural communities to promote Climate Smart Agriculture, including introducing new growing techniques, sourcing improved seeds, trialling alternative crops, and implementing soil protection practices. We also work to strengthen links with the private sector to facilitate access to supplies and equipment.

Agriculture is often an integrated component of larger Concern programmes. For example, our Graduation programme takes a multi-pronged approach to giving families the education, training, and funding they need to achieve financial independence. Since so many of the families participating in Graduation work in farming, there’s often a large focus on CSA and other techniques to help their farms become more successful. For this reason, it’s also a key focus in our work around building nutrition and ending hunger. Here are a few recent examples of our work over the last year:

- In the arid- and semi-arid lands (ASALs) of Kenya, we supported over 6,400 families with training on nutrition-sensitive and Climate Smart Agriculture, enabling them to produce a diverse range of crops and contributing to a significant reduction in childhood malnutrition.

- Also in Kenya, the LEAF Project (Lifesaving Education and Assistance to Farmers) provided families with similar CSA training as part of a larger Graduation-style programme. For the first time in three decades, there was no need for humanitarian food distributions among 20 communities in the Tana River County area.

- In Syria, where agriculture and livestock powered the local economy before the war, our intervention for conflict-affected farmers in the north reached over 60,200 people, restoring their livelihoods and improving food security through cash transfers, land cultivation training, and livestock distribution.

- Our integrated community resilience programme in Chad reached over 43,000 people and reduced the number of months during the hunger season from 2.57 to 2.12 through a combination of conservation agriculture, market gardening, natural resource management, improved stove making, and livestock management.

- In the Tahoua region of Niger, our Realigning Agriculture to Improve Nutrition (RAIN) programme focuses on improving food and nutrition security, and reached over 9,200 last year. One key element of the programme is gender equality, reducing the inequalities experienced by women and girls so they are active agents in building a future for themselves and their communities.