Read our 2023 annual report

Knowledge Hub

In advance of this year's Women of Concern, honouring Irish-Somali activist Ifrah Ahmed and her work to end female genital mutilation (FGM), we are sharing this story, which originally appeared on Concern Worldwide US's website in 2018.

Despite being outlawed in Kenya in 2011, female genital mutilation (FGM) remains a pressing issue in the country, largely due to traditional beliefs and practices. Also known as female circumcision (and generally used as a term to cover any practices that inflict damage to female genitalia for non-medical purposes), cases of FGM in Kenya now come with a minimum three-year prison sentence, a fine of approximately €2,000 — or both. However, a law is not enough, and many Kenyan girls still undergo this painful, and dangerous, process in order to maintain their social standing and, eventually, improve their chances of a good marriage.

While many Kenyans support ending FGM, research suggests that the best bet for making this happen is through locally-led initiatives. In 2018, we saw one of those initiatives in action, led by a then-12-year-old girl in Marsabit county.

“It happens to nearly 100% of the girls here”

Marsabit is one of those areas of northern Kenya where FGM has been the rule rather than the exception. “Here, it’s very common for FGM to be carried out on girls as young as 9 or 10 years old,” explains Concern Kenya’s Education Manager, Agnes Angolo. “In fact, it happens to nearly 100% of the girls here.”

Once that happens, Angolo adds, “they’re generally married off and become pregnant — which means they no longer go to school.” Many of them go on to have daughters who repeat the cycle, keeping it in play from one generation to the next.

Against the flow

But 12 year-old Botu had other ideas. “I am not ready to be a mother,” she explains firmly. “If I become pregnant, I will not be able to realize my dream of becoming a teacher.”

To challenge centuries-old tradition held as sacred in your community is a very, very difficult thing to do. But it was when Botu sat with Angolo in an after-school club meeting that she realized she had a choice to do just that.

“Initially, I had planned to take Botu to undergo the process [of FGM] so that she would not be termed an outcast,” says Chiluke, her mother. “But she refused. She wanted to be an example to others.”

“If I become pregnant, I will not be able to realize my dream of becoming a teacher.”

Leading locally

This is where other local initiatives to change attitudes surrounding FGM in Kenya helped to strengthen Botu’s case. A study in the journal Reproductive Health notes several ways community-based approaches can help curb this practice, including finding alternative ritualistic programs (ARPs) to symbolize a girl’s transition into womanhood, engaging men (especially fathers) as allies, and strengthening community accountability and policing.

Much of this, however, begins by helping communities understand the dangers of FGM. At the time of Botu’s decision, a local politician had begun to hold meetings in the area to do just this, discussing FGM as both a threat to the health and safety of girls and women, as well as a barrier to girls achieving a full education. Chiluke, who herself had undergone the process when she was Botu’s age, attended one of these meetings with an open mind. She decided to support her daughter’s choice.

“Botu’s bravery encouraged me to decide to protect her against FGM,” Chiluke says. It wasn’t a welcome decision in their community, but Chiluke notes that “being a single mother [meant] it was easy for me to stand my ground, since I would make decisions that would favor my daughter.”

A little revolution…

The story doesn’t stop there for Botu who is, as she says “now a champion of this cause.” In some ways, her dream of becoming a teacher has already come true: “I use the information I have to explain the dangers of FGM to other girls and I encourage them to resist. I talk to boys about it too!” she adds.

And this little revolution is growing roots. Chiluke explains that three of her friends have daughters of Botu’s age and they, too, have decided to opt out of FGM for their girls. These women are also single mothers, but it would appear they are not alone. “Other surrounding neighbors are now resisting the practice — although not openly,” Chiluke says

…and a bigger picture

This is just one story of the women (and men!) in Kenya who are working to put an end to FGM — something President Uhuru Kenyatta had initially pledged to do by 2022, although the pandemic has made that goal all but unlikely. However, Botu’s story demonstrates the old adage: “If you want to go far, go together.” Her choice was informed by what she had learned in school and at Concern’s after-school program. It was strengthened by the independent work of a respected political leader, and her mother agreeing to also learn more about the topic through that work.

Change takes support at all levels, and Botu is now one of those forms of support. Some day, she also hopes to become a mother and pass that support on to the next generation within her community — just not yet. She has dreams to realize.

Concern and gender equality

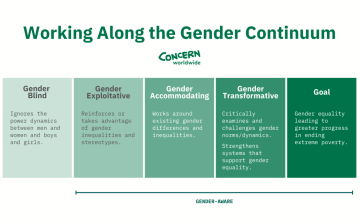

All of Concern's programs are fortified by a commitment to gender equality and gender transformation. The closer we can get to work that’s transforming gender inequality versus simply being aware of it, the closer we can get to actual, sustainable equality.

For every €1 donated to concern, 93% goes directly into our programming in 25 countries around the world. Last year, you helped us reach over 20 million women and girls. Help us do even more this year.