Read our 2023 annual report

Knowledge Hub

Food security is when all people at all times have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and preferences for an active and healthy life. Here’s what that really means.

The world produces enough food to feed everyone on the planet. However, the basic human right to food security is a right that goes unmet for approximately 10% of the world’s population. But what do we actually mean when we talk about food security?

A term first defined in 1996 at the World Food Summit, food security is defined when all people at all times have physical and economic access to sufficient, safe, and nutritious food; food that meets their dietary needs and preferences and helps to fuel an active and healthy life.

Read on to learn more about what that actually means, how we measure food security, and some of the issues that are preventing everyone from enjoying this most basic human right.

The four pillars of food security

The definition of food security is pretty specific, giving us something that can be measured in a way that we can’t always do with a concept like hunger (though you can learn more about how we measure hunger at Concern). Food security is measured around four key dimensions or pillars: availability, access, utilisation, and stability.

1. Availability

The physical availability of food in a community or area. This can vary based on food production in an area, supply levels, and trade routes.

As one example of where availability can be an issue, we can look to Somalia’s wheat supplies. Like many countries, Somalia has typically relied on Russia and Ukraine for the majority of its wheat imports, a supply chain that was interrupted with the escalation of conflict in 2022.

2. Access

If there is enough food in an area, there still may be questions of both physical and economic access. True food security means that people have the resources they need to get a sufficient amount of quality food.

To go back to Ukraine for an example, one of the ways that conflict has affected food security within the country is through access. Approximately 25% of the country’s population currently lives below the poverty line (itself a 25% increase since the start of the conflict). The combination of low incomes and inflation have made it hard to cover basic needs, including groceries, which are physically available but economically out of reach.

3. Utilisation

This is where we get into the quality of food and how the body utilises the nutrients and energy provided by what’s eaten. This comes down to the nutritional diversity and quality of the food itself, as well as in how people prepare it and how it’s shared among a family.

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, clean water is a major issue, with less than 50% of the population having access to basic water services, and only 15% having adequate sanitation. This means that, even with a diverse array of food options, the meals can mean nothing if they’re prepared with contaminated water that prevents the body from absorbing nutrients.

4. Stability

These other three pillars are irrelevant if available, accessible, and well-utilised food is not stable within a community — meaning that people can get what they need when they need it.

We see this issue come up a lot in communities that rely predominantly on agriculture for both their livelihoods and own food supplies. Many of these communities experience what’s known as a hunger season in between their last harvest running out and their next harvest happening, a period that can last months (especially if a drought or flood reduces a harvest’s yield or damages supplies).

How do we measure food security?

Much like hunger, there isn’t one set method for measuring food security. However, the definition and pillars give us a few key areas to focus on. The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) uses its own Food Insecurity Experience Scale, which is based on asking participants eight simple questions that increase in severity, allowing the FAO to plot answers on a scale.

According to one academic paper from 2023, which surveyed 78 articles on food security to determine the most popular indicators, the level of diversity, number of calories consumed, and experiences of food insecurity are among the most commonly used. However, the best measure of food security will account for all four pillars.

The Integrated Food Security Phase Classification (IPC), another key resource for tracking food insecurity levels, does this by analysing food consumption levels, changes in livelihoods, nutritional trends, and mortality rates and then triangulating these with factors like availability, access, and hazards at the local and national level.

Does food insecurity mean a famine?

The IPC sets different levels of food security, which many organisations use as a standard for understanding where hunger levels are at their worst. This can be within an entire country, but more often than not a food security crisis is more localised based on a host of factors including conflict, natural disasters, time of year, and average family income.

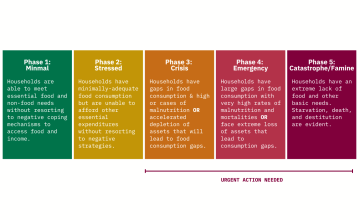

We cover this more in our famine explainer, but the IPC ranks food security across five categories:

When we talk about people being at crisis or emergency levels of food security, we’re referring (respectively) to IPC Phases 3 and 4. (Famine ranks at Phase 5.) However, many families fall into IPC Phase 2, which is when food security is “stressed,” meaning that they can afford the bare minimum but may not be able to get other essentials.

It’s a lot easier to move from Phase 2 to 1 than it is from Phase 4 to 1. In order to end hunger and food insecurity, it’s equally important to ensure that these families move from Phase 2 to Phase 1 (no or minimal insecurity) rather than moving into Phase 3 or 4.

Building food security will end hunger

Ultimately, what all of this comes down to is the fact that ending hunger means establishing food security, especially in communities that are most vulnerable to risks like conflict or climate change.

Concern works towards this every day, to some degree in each of the countries where we work. Emergency food supplies or cash transfers that allow people to shop locally are key aspects of responding to a crisis, like the outbreak of conflict or an earthquake, as these shocks can set vulnerable families back to a high degree otherwise.

We also work on longer-term projects that enable families to build their own resources and safety nets — financially and agriculturally. Having more diverse income sources in an agricultural community means that there are options to fall back on in case of a bad harvest or a devastating cyclone. Climate Smart Agriculture helps farmers mitigate risks against droughts or other natural disasters.

Other programmes work with families to find more sustainable and creative ways of preserving food to last through the lean seasons while maintaining its nutritional content.

Learn more about the countries hit hardest by food insecurity, the causes of food insecurity, and some of the other ways we address it through the articles below.

Other ways to help

Corporate support

Is your company interested in working together for a common cause?

Fundraise for Concern

From mountain trekking to marathon running, cake sales to table quizzes, there are lots of ways you can support our work.

Buy a gift

With an extensive range of alternative gifts, we have something to suit everybody.

Leave a gift in your will

Leave the world a better place with a life-changing legacy.

Volunteer with Concern

The lots of ways to get involved with our work as a volunteer

School fundraising

Without the generous support from schools, we wouldn't be able to do the work that we do.