Read our 2023 annual report

Knowledge Hub

Bangladesh may not have competed in the 2022 Winter Olympics, but it did recently secure a top position among South Asian countries working towards gender equality.

In the World Economic Forum’s 2021 Global Gender Gap Report, it scored 0.719, making it one of the top countries in the region for closing the gender gap. It also ranks number seven in the index’s sub-ranking of political empowerment, and holds the distinction of being the only country where more women have held head-of-state positions than men over the past 50 years.

But there’s still a lot of work to be done. Here’s a look at the gender inequalities in Bangladesh that need to be addressed, and how Concern is working to close some of those gaps by engaging male allies.

Gender inequality in Bangladesh by the numbers

- Bangladesh ranks 133 out of 162 countries on the UNDP 2020 Gender Inequality Index

- 51% of Bangladeshi women aged 20-24 were married before their 18th birthday

- 15.5% of Bangladeshi women aged 20-24 were married before their 15th birthday

- In the last year, nearly 25% of all Bangladeshi women and girls have experienced physical and/or sexual violence by a current or former partner

- 7.2% of women in Bangladesh who have work still live below the poverty line

- Unemployment rates for women in Bangladesh are double those for men: 6.7% of women are unemployed, while only 3.3% of men are unemployed

- 173 out of 100,000 women in Bangladesh are expected to die due to complications from pregnancy or childbirth

Gender inequality is strongly linked to poverty in Bangladesh

While Bangladesh scores high for women in politics, it’s still one of the toughest countries to be an employed woman. The WEF’s 2021 Global Gender Gap Report shows a gap of 88% between the number of men and women in managerial positions. 2016 labour force participation rates show that 81.9% of men in Bangladesh work, while only 35.6% of women do.

Of these men and women who are employed, over 95% of women are informally so. Jobs as wage labourers, self-employed, or unpaid family caregivers are common, but mean that less than 5% of Bangladesh’s female workforce have a safety net in terms of paid leave, unemployment, and social security should they be sick, laid off, or otherwise unable to work for a period of time. This leaves the country ranking 147 out of 156 in terms of economic advancement and opportunity for women.

Gender-based violence is another major barrier to gender equality

Despite laws designed to protect women and girls, gender-based violence (GBV) is all too common in Bangladesh. Statistics on GBV in Bangladesh went largely unreported until about a decade ago, when the UNFPA worked with the country’s National Statistical Office to complete the first-ever Violence Against Women Survey. In that survey, 87% of women who were or had been married reported some experience of GBV in their lifetime.

This wasn’t an isolated number. In the first nine months of 2020, at least 235 women were murdered by their husband or his family, according to local human rights group Ain O Salish Kendra (ASK). Another Bangladesh-based NGO, BRAC, documented a nearly 70% increase in violence against women and girls during the country’s 2020 lockdowns due to COVID-19. Further killings and acid attacks (a common form of gendered violence in the country) have been reported, largely due to rejected sexual advances or marriage proposals, dowry and disputes, or as a punishment for seeking education or work.

Cultural norms have led to harsh economic and social realities

Bangladesh is in the middle of implementing several laws and policies to protect women and girls and their basic human rights. However, as Human Rights Watch notes, there are several challenges to the success of these laws, including a failure in accountability and poor enforcement.

We can trace a lot of this back to Bangladesh’s patriarchal and patrilineal traditions. This is by no means a recent discovery; a 1979 article in the Population and Development Review states:

In rural Bangladesh, patriarchy interacts with economic class to produce a rigid division of labor by sex, a highly segregated labor market, and a system of stratification that places women at risk of abrupt declines in economic status independent of the processes of class differentiation.

Despite significant strides towards gender equity in the last 43 years, these attitudes have not fundamentally changed. A 2020 paper for the Electronic Research Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities echoes the 1979 PDR report:

In Bangladesh, it has been a common scenario that men dominate, oppress, and exploit women, and it is accepted by the social institutions because of their patriarchal structure. In the family, women are considered as passive dependents and property of their husbands.

In order to change the other elements of gender imbalance, it’s clear that we need to first change attitudes towards gender.

Engaging men and boys

A growing body of evidence has affirmed that engaging men is key to achieving gender parity. From GBV to avoiding domestic work and caregiving duties, men’s behaviours are influenced by social norms. These norms are also shaped around views of masculinity. Men play an essential role in challenging the patriarchal beliefs and practises that promote the subordination of women. However, in many of the areas where Concern works, questioning these gender norms can be risky for men.

Knowing that this was a widespread issue and that community empowerment was one of the keys to breaking the taboos of social stereotypes, we began to look for ways to bring groups of men together as part of a broader, healthier, safer, and richer cultural experience. In 2012, we increasingly began involving men as allies to promote gender equality and creating spaces to explore the effects that patriarchy has on their own lives and opportunities. Concern’s approach to Engaging Men and Boys (EMB) is based in part on the experience and expertise of organisations including Promundo, MERGE for Equality (formerly known as Men’s Resources International), and Sonke Gender Justice. It’s also one element of our larger gender equality work in any given community.

Engaging Men and Boys in Bangladesh

What does it really mean to be a man or a woman? This is the focus of the conversations that begin most EMB programs, including the one Concern has implemented in Bangladesh. A three-day training for both male and female Change Makers in Dhaka included discussions of:

- Sex

- Gender

- Gender equity and equality

- What men and women typically do over a 24-hour day

- Forms of power

- How we learn violence and the different types of violence

- Violence against women

- What it means to “act like a man” or “act like a woman”

- Positive parenting

Concern Bangladesh staff undergo similar trainings so that we have an equal level of understanding across all team members on the concept of gender equality and all that entails. These conversations allow us to get to both the root causes and effects of gender inequality — including GBV — and internalise them. Our Change Makers then become advocates for gender equality within their communities, and work with other groups including Mothers Support Groups, Self-Help Groups, and adolescent groups, to affect change from within. What we see with this approach is that it’s much easier to create sustainable “buy-in” from community members when these challenges to traditions and common attitudes come from within.

Change Makers also advocate with local-level community leaders, ward health and development committees, religious leaders, teachers, and government institutions, helping to build the accountability and enforcement needed for Bangladesh’s gender equality laws to hold up and serve the people they’re designed to protect.

They told us to give equal importance to both sons and daughters. They told us to not feed our daughter less food just because she’s a girl. An educated girl can do much more than a boy to help her parents. If I educate my daughter well, she will support me one day.

Working with local partners and leaders

In Bangladesh, Concern has worked towards gender equality advocacy with a number of local organisations, including the Men and Boys Network Bangladesh, the National Girl Child Advocacy Forum, Citizens' Initiative for Domestic Violence, SEEP, the Sajida Foundation, and Nari Maitree. Our EMB work has included these partners, as well as program participants in the Irish Aid-funded programme “Improving the Lives of Urban Extreme Poor” (ILUEP, run from 2017 to 2021).

With technical support from Sonke Gender Justice, our programme team systematically applied the EMB approach to ILUEP and worked with Change Makers to address gender-based violence and bring about meaningful, sustainable changes in gender norms.

If my wife says something angrily, I should leave the house without replying and walk around outside for some time to calm down and return home. This will cause anger on both sides to dissolve and we can discuss things calmly. After learning from the training, we are using this in our real life. By doing this, our family problems have decreased a lot.

At the end of last year, Change Makers showed both the capacity and confidence in handling violence and family conflicts, working in cooperation with Ward Councillors, community leaders, and — when necessary — law enforcement. They are also actively advocating for several priorities they’ve identified around fostering gender equality around Dhaka, including preventing sexual harassment, ensuring basic healthcare is available for women along with WASH services, and helping women find safe and dignified livelihood opportunities.

The results of EMB

Through the ILUEP programme, Change Makers and community members prevented 84 cases of child marriages between 2017 and 2021. In that time, they also worked with 53 Ward Committees towards gender-transformative initiatives, including some of the priorities mentioned above.

Community-based gender discussions and trainings led by Change Makers have also led to quantitative shifts in attitudes: When asked if women should be involved in making decisions with men in the family at the start of EMB, only 35% of participants agreed. In 2020, 82% of participants agreed. Likewise, when asked if childcare is a shared responsibility between women and men, only 24% of people agreed at the beginning of the programme. In 2020, those surveys showed that 60% now agree.

Concern and gender equality

Gender equality is one of the most important steps to ending extreme poverty. The United Nations identifies gender equality as Goal #5 of its 17 Sustainable Development Goals to hit by 2030. To reach this, our approach at Concern is to address the root causes of gender disparity. Many of these causes are similar to the factors that perpetuate global poverty and hunger.

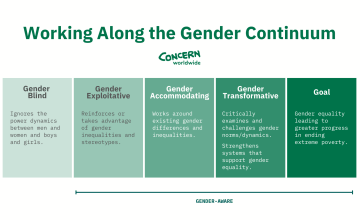

The closer we can get to work that’s transforming gender inequality versus simply being aware of it, the closer we can get to actual gender equality.