Read our 2023 annual report

Knowledge Hub

It seems like millions of people across Africa are constantly on the brink of famine. This doesn’t have to be the rule.

In the final months of 2022, 70% of the world’s hungriest people are located in just three countries: Ethiopia, Kenya, and Somalia. The current crisis in the Horn of Africa following several failed rainy seasons has exacerbated hunger in the region, affecting more than 36.1 million people. However, this isn’t the only reason that these three countries — which account for roughly 2% of the global population — face disproportionate levels of hunger.

The Horn of Africa is also not the only part of the continent to be facing higher hunger levels than many other parts of the globe. In fact, seven of the 10 hungriest countries in the world are located here, spread out across different regions.

But does it have to be this way? Let’s take a look at the current hunger crisis in Africa: what’s going on now, how we got here, and what can be done both in the short- and long-term to solve it.

Hunger in Africa: What’s going on right now (and where)?

According to the 2022 Global Hunger Index, out of 54 countries, 37 African countries have levels of hunger that are rated “serious” or higher.

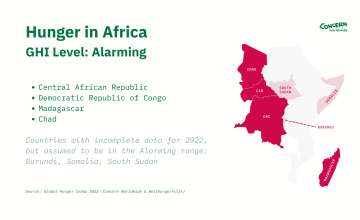

Hunger level: Alarming

Four countries in Africa rank among the hungriest: Central African Republic, Chad, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Madagascar all rank at “Alarming” levels of hunger in the 2022 GHI. (Countries with incomplete data for 2022 but assumed to be in the “Alarming” range are Burundi, Somalia, and South Sudan. Last year, Somalia ranked as the world’s hungriest country with the only “Extremely Alarming” GHI ranking.)

In 2022, the Horn of Africa is at the centre of a food crisis due to an ongoing drought — the worst the area has seen in more than 40 years. However, that’s only part of the story for Somalia, which has experienced a cycle of crisis for more or less the same amount of time. Decades of civil war, combined with climate change, forced displacement, and political instability, have led to a complex humanitarian crisis that has weakened the national health system.

Similar forces are at play in Burundi, CAR, Chad, DRC and South Sudan—all of which have faced at least 10 years (if not more) of protracted violence that has weakened infrastructures, leaving food shortages to spiral out of control.

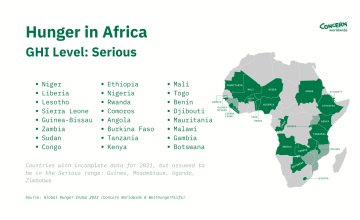

Hunger level: Serious

If we overlapped the “Serious” hunger level map with the “Extremely Alarming” and “Alarming” maps we’d see that the majority of the continent would be covered, with many food insecure countries covering areas in the northwestern, southwestern, and eastern regions of the continent.

The Sahel area—which includes Mauritania, Mali, Burkina-Faso, Niger, and Nigeria—has seen food shortages as weather patterns become more erratic. Climate vulnerability in the desert region has left experts predicting a devastating temperature increase between 2.0 and 4.3 °C by 2080. Cross-border violence has made food security even more untenable. Further south, countries like Liberia, and Sierra Leone may be at peace, but are still rebuilding following civil wars that ended at the beginning of the 21st century. Much of that reconstruction was halted here between 2014 and 2016 due to the West African Ebola epidemic.

Hunger in Africa: How did it get so bad?

Conflict, political instability, and climate change consistently come up when we look at the parts of Africa facing serious levels of hunger. Here’s a bit more on how things got to the point they are today.

High reliance on agriculture and pastoralism

Many of the countries facing high levels of hunger in Africa today are also countries where the majority of residents rely on agriculture and pastoralism for their livelihoods. Smaller-scale subsistence farmers also rely on their harvests to eat. If they’re in an area where crops and grass have dried up, they are often forced to find better pastures, which can create a run on already-scarce resources. The large-scale effects of climate change on crops has also left many low-income and remote families without resources to build resilience against natural disasters. If this is their only source of food or income, they don’t have much — if anything — to fall back on during a drought, flood, or other natural disaster.

Climate change and the depletion of natural resources

The Global Adaptation Initiative index ranks Chad as the most vulnerable country to climate change, accounting for the country’s exposure to climate events and its lack of preparedness for the effects of the climate crisis. This isn’t a longstanding phenomenon. Likewise, Niger has faced ongoing, multi-year droughts since 1968. The World Bank reports a decline in harvest size and quality since that time as well.

These are just two examples, but they represent a larger issue within Africa. During the continent’s colonisation by European superpowers, many of its countries saw their natural resources depleted by those countries, which were undergoing periods of industrialisation. Many of those net effects have just come up in the last half-century. Deforestation has turned many areas into “heat traps” for the sun (which can hit hard in countries around the Equator), and desert areas have become more vulnerable to frequent floods since their terrain isn’t designed to absorb water.

The decolonisation process

Colonisation of Africa often left certain areas of countries underdeveloped, such as the part of Sudan that became present-day South Sudan—which, while under British rule, was under-resourced as more money went into the north (what is still present-day Sudan). Almost worse were the states in which many countries were left when they gained independence—particularly those who did so during the late 1950s and early 1960s African Independence movement; when countries like the United Kingdom, Belgium and France left territories like Sierra Leone, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Central African Republic without a sense of political stability or trustworthy democratic processes.

Let’s take the DRC, which gained independence from Belgium in 1960, as an example. In May of 1960, Patrice Lumumba was elected the DRC’s first Prime Minister. Four months later, he was overthrown in a military coup led by Col. Joseph-Désiré Mobutu — who received assistance from both Belgium and the United States and ruled as a dictator for 36 years (Lumumba was executed in early 1961). His rule came to an end in 1996 when he was deposed during the First Congo War, although his successor — Laurent Kabila — was then faced with the challenge of the Second Congo War, which began with a rebellion led by ethnic minority forces and ended in 2003. The DRC still feels the effects of that war, with ongoing violence, authoritarian leadership, extreme poverty, and some of the highest levels of hunger in the world.

Hunger in Africa: How can it be solved?

Obviously, there isn’t one catchall solution to the problem. However, there are proven short- and long-term solutions to hunger in Africa that, when taken together — along with a few other elements — could lead to the continent reaching Zero Hunger.

Short-term: Treating malnutrition

To keep a hunger crisis from spiralling into a famine, we have to address the most severe cases first. That usually means treating acute malnutrition (especially in children). This is where Community Management of Acute Malnutrition (CMAM) and programmes like it come in.

Using ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), CMAM takes a community-based approach to screening and treating malnutrition, meaning that families can get treatment often from the comfort of their own home and that children undergoing treatment have greater survival and recovery rates.

New iterations of CMAM, such as CMAM Surge, help to proactively respond where we know there are higher rates of food insecurity and malnutrition. But from there, we also need to find other ways of increasing a family’s food security beyond emergency treatments and food aid packages.

Short-term: Improving farms

Since a large population of Africans are subsistence farmers — meaning that they rely on the land for their food as well as their income — and since many of the countries hit hardest by climate change are in Africa, that often involves some degree of Climate Smart Agriculture or other resilience-focused work to help increase the quantity and quality of harvests. This includes training, giving people access to clean water, tools, seeds, and cash to keep their family farms afloat. Many families also need better food storage and preservation systems than are currently available to them so that they can extend the shelf-life of their harvests.

Africa is also home to some of the world’s largest refugee crises and hosts large camps of internally-displaced people, meaning that cash grants and food vouchers are even more critical as land in these settlements is often at a premium. Kitchen gardens, sack gardens, and keyhole gardens can help from one season to the next.

Medium-to-long-term: Improve water and sanitation services

This is a bridge between many of the short-term responses to hunger and those that will take longer. Some water and sanitation projects can be quickly and nimbly done — such as trucking in fresh water to areas suffering drought. Others can take much longer, but create an ongoing system of clean water and sanitation in a community.

Africa is also host to some of the most water-stressed countries. That carries huge implications for hunger and malnutrition levels. This helps families sustain their crops and herds. More importantly, reducing the risk of diarrhoea and other waterborne illnesses means that people will be better-equipped to absorb the nutrients of the food they’re eating.

Long-term: End conflict

In adding up the cost of ending world hunger, Concern Worldwide’s Policy and Advocacy Manager, Makayla Palazzo, explained that the cost of feeding everyone who is food-insecure for however long only goes so far: “They’d just be hungry again once the aid ran out. Hunger is caused by bad policies and conflict. Unless those are addressed, it won’t ever end.”

The legacy of colonialism in Africa — combined with many other factors — has contributed to a legacy of protracted conflict. The Geneva Academy records more than 35 armed conflicts currently taking place across the continent, including Burkina Faso, CAR, DRC, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan. Other countries not technically at war are still susceptible to violence and instability (especially along border regions). It’s a tall order, but the links between conflict and hunger are inarguable. We can’t end one without ending the other.

Long-term: Curb greenhouse gas emissions and commit to climate justice

Most of the countries hit hardest by the climate crisis and facing increasingly erratic weather patterns and more destructive weather events are those that have contributed the least amount of greenhouse gas emissions. While 195 countries signed the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015, many (including the United States) are falling short of their commitment to reducing their carbon footprints. In addition to curbing the human activities that cause climate change, however, we also have to commit to climate justice — including funding — to support the most affected people and areas, many of which are in regions like the Sahel and Horn of Africa.

Long-term: Overhaul political policies

Many of the other changes that need to happen before we can end hunger need to be codified and enforced at the political and legal levels. Gender inequality, for instance, is a huge driver of hunger (especially in Africa, where many countries still have laws upholding harmful patriarchal structures). It’s not enough to ban gender discrimination and gender-based violence; these laws must be upheld at the local, national, and international levels. The same goes for policies specifically aimed at reducing hunger. Access to enough food to get through each day is a fundamental guarantee in the UN’s Declaration of Human Rights, and world leaders must make good on that guarantee.

Hunger in Africa: Concern’s response

Concern currently works in 15 countries across Africa. Health and nutrition are key aspects of our response in each country, and we address the hunger crisis in Africa largely through our award-winning CMAM programme as well as initiatives like Climate Smart Agriculture. In conflict and crisis settings, we also work on distributing essentials like food kits and nutrition screenings.

We tailor many of these tried-and-true approaches to the specific needs and conditions of the communities we serve. For example, we paired CMAM with our Graduation programme in both Ethiopia and Kenya for the LEAF Project. Funded by Archer-Daniels-Midland, LEAF (Lifesaving Education and Assistance to Farmers) addressed both the short-term needs of malnutrition in communities, while helping participants to improve their farming practices in response to the new realities brought on by climate change. In 2021, for the first time in three decades, there was no need for humanitarian food distributions among the 20 communities in Kenya’s Tana River County that participated in LEAF.

Drawing on over 50 years of experience in nutrition programming, Concern recently developed ERNE (Enhanced Responses to Nutrition Emergencies). This three-year, EU-funded programme treats severely-malnourished children while simultaneously strengthening local health systems’ abilities to respond to (and even prevent) surges in malnutrition. A pilot programme is running in five countries — the DRC, Ethiopia, Niger, South Sudan, and Sudan — and in its first year reached over 342,000 people.