Read our 2023 annual report

Knowledge Hub

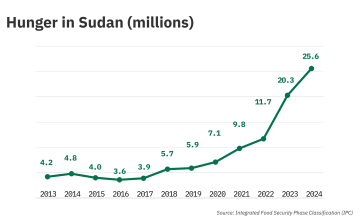

Almost two years of conflict in Sudan has created the world’s largest hunger crisis and now famine has been detected in at least five parts of the country.

In Sudan, hunger is at catastrophic levels as we mark the beginning of 2025.

Famine has now been detected in five areas across the country. the IPC Famine Review Committee (FRC) is predicting that five more areas will face famine before May 2025, with a risk of famine in 17 additional areas.

Furthermore, more than 24.6 million people are facing high levels of food insecurity between December 2024 and May 2025. This represents a start increase of 3.5 million people compared to the original projection, and corresponds to over half of the entire population of Sudan.

Health services are critically limited, with a massive 70% of facilities labelled dysfunctional and unable to meet the needs of the Sudanese population.

One of North Darfur’s largest displacement sites, Zamzam is home to over half a million people fleeing violence who are unable to leave, farm, or afford the food staples and other commodities that are available to them in the area.

Read on for what that means, how we got here, and everything else you need to know about the current hunger crisis in Sudan.

Sudan is facing its highest levels of hunger on record

As reported last summer, Sudan “is facing the worst levels of acute food insecurity ever recorded by the IPC in the country.” When the IPC declared famine in August, hunger levels in the country were especially high as it was in the middle of the lean season between harvests. The famine-monitoring network estimated then that conditions would continue into the end of October (at the end of the lean season).

However, that doesn’t mean that we’re past the worst of the crisis. Indeed, the IPC initially said that the likelihood of the famine continuing into the new year was “high,” and has since added that “the likelihood of famine remains high in Zamzam camp after October and that many other areas throughout Sudan remain at risk of famine as long as the conflict and limited humanitarian access continue.”

Before the latest IPC projections, it was estimated that 21 million people were facing high levels of acute food insecurity. This included nearly 109,000 facing famine conditions (IPC Phase 5), with 6.38 million facing emergency levels (Phase 4) and nearly 14.6 million facing crisis levels of hunger (Phase 3). Now, those numbers are proving even more stark.

The most extreme levels of hunger are concentrated in all five states of Greater Darfur, as well as South and North Kordofan, Blue Nile, Al Jazirah, and Khartoum.

“People are having to eat leaves and mud for energy just to try to survive,” says Concern Sudan country director, Dr. Farooq Khan, of the current situation. “The suffering is so egregious they don’t even have the energy to shout aloud or ask for help anymore.”

How did it get so bad?

Hunger was an issue in Sudan even before conflict broke out in April 2023. At the end of 2019, approximately 5.9 million Sudanese were facing chronic hunger. An estimated 80% of all stunted children lived in just 14 countries. This included Sudan, where extreme poverty, inadequate feeding practices, and the effects of climate change were key drivers for high malnutrition rates, leaving just over 14% of all Sudanese children under the age of five acutely malnourished.

The knock-on effects of the early years of the pandemic didn’t help matters. Border closures affected the supply chains for staples like wheat and vegetable oil, a problem for a country that relies on imports for roughly 25% of its essential food supplies. Emergency supplies were quickly depleted, and many of the most vulnerable Sudanese lost or saw drastic reductions to their incomes and livelihoods as a result of closures and inflation. The situation worsened in 2022, following the invasion of Ukraine (Sudan relied on both Russia and Ukraine for some of its essentials, including wheat).

At the end of 2022, one year into a shift in political leadership and amid ongoing instability and uncertainty, the IPC estimated that as many as 11.7 million people were facing food insecurity. This represented a nearly 100% increase in hunger levels pre-pandemic, and a 225% increase compared to 2016, which had the lowest levels of recorded food insecurity in Sudan over the last decade.

How conflict doubled the hunger rates

The crisis in Sudan escalated on April 15, 2023, with violent clashes between rival factions in the capital of Khartoum sparking a nationwide conflict and massive displacement, both within Sudan and in neighbouring Chad.

For those who have remained in Sudan, food shortages have become a fact of life. The Food and Agriculture Organisation estimates that food production fell by 46% in the first year of the conflict as people were driven from their homes or unable to safely work their farms (agriculture accounts for 80% of employment in Sudan).

Food processing factories ceased operations due to the war, and the only factory in the country that produced lifesaving ready-to-use therapeutic food (RUTF), the standard treatment for childhood malnutrition, was destroyed.

Fighting has been especially intense in Darfur and Al Jazirah, the region known as Sudan’s bread basket. Adding insult to injury, the World Food Programme warned last year that Sudan was unable to afford to import enough food to cover the shortage due to hyperinflation.

What food is available in the country is too expensive for many of the most vulnerable Sudanese families (particularly those displaced by conflict). In its analysis of Zamzam camp, the IPC noted that the camp’s main market was functioning intermittently, with irregular deliveries made at high risk to those carrying them through unsafe areas. This has contributed to the price spikes of available goods.

“People are selling off their assets to buy food for their families. Supplies to commercial markets have been disrupted by the fighting. Many people are now totally reliant on aid in order to have just one meal a day,” explains Dr. Khan.

People are selling off their assets to buy food for their families. Supplies to commercial markets have been disrupted by the fighting. Many people are now totally reliant on aid in order to have just one meal a day.

It’s not just about the food

Food security is a key focus in mitigating the effects of the conflict in Sudan. However, this is just one piece of the puzzle. Healthcare facilities have also faced attacks since violence broke out. As malnutrition rates continue to rise, this means that many Sudanese (especially children) will face an additional challenge: receiving adequate medical care.

“We continue to face challenges in the movement of goods and staff into and across the country,” says Amina Abdulla, Concern’s regional director for Horn of Africa. “It is only a matter of time before we run out of supplies in the various health facilities that we support and services come to a halt despite the ever-increasing levels of needs across the country.”

“The 90 clinics we are supporting are under stress,” adds Dr. Khan.

Conservative estimates are still staggering

In a world overrun by conflict and crisis, humanitarian agencies are wary of making hyperbolic statements.

However, in a March 20th 2024 speech to the Security Council, the UN’s Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) Edem Wosornu warned of “a far-reaching and fast-deteriorating situation of food insecurity in Sudan.” At the one-year mark for the conflict, 18 million people were facing high levels (Crisis, Emergency, or Catastrophe-level) of food insecurity.

By the summer of 2024, those numbers had risen by more than 40%. Dr. Khan says that even this may have been a conservative estimate: “From the feedback we [received], the IPC could [have been] under-reporting the situation by 5-10%.”

Displacement is also a significant issue in the fight against hunger and starvation. It is now being reported that more than 11.5 million people across all 18 states in Sudan are displaced - put in other terms, more than a quarter of all Sudanese people have been forced to flee their homes, making a bad humanitarian situation far worse.

What has happened since August?

Since famine was confirmed in August, Sudanese authorities reopened a critical crossing between Sudan and Chad in Adre, the shortest and most effective route for getting humanitarian assistance into the country according to the WFP. The first crossings in six months took place in late August.

The reopening made it possible to deliver larger quantities of critical humanitarian aid to western Sudan, and in the first ten days alone 59 trucks carrying medical, food, shelter, and other essential items crossed the humanitarian corridor, reaching nearly 195,000 people. However, this is a drop in the bucket compared to the roughly 36 million people in the region (including neighbouring Chad and South Sudan) who require food and nutritional support.

Further complicating matters, heavy rains, flooding, and ongoing insecurity in September and October delayed the movement of vital aid and made clinics and distribution points harder to access. The rains also fueled rising cases of malaria and cholera.

“This is the world’s largest humanitarian crisis which is continuing to deteriorate each day,” says Dr. Khan. “A major response by the international community is needed to make the warring parties provide access to humanitarian organisations, across national borders and military frontlines.” Dr. Khan adds that funding continues to be a major barrier to effectively delivering aid and avoiding a major humanitarian catastrophe: As of September, just 41% of the required funds for baseline aid in 2024 had been provided.

Hunger in Sudan: What can be done?

At the moment, the two biggest challenges to the hunger crisis in Sudan are political and financial. However, that doesn’t mean the situation is hopeless.

“Despite insecurity, complex and costly logistics, and bureaucratic impediments hindering the international response, communities and humanitarian organisations are responding - and much more can be done if the resources are provided,” says Dr. Khan.

The IPC estimates that conditions will continue as they are in Zamzam and the surrounding area (El Fasher), with trade flows and humanitarian access severely interrupted, well into the new year. While the rainy season began in October and may have made foraging for wild foods a bit easier, this will have left people vulnerable to attacks and ongoing violence. The start of the rainy season will have also accelerated waterborne and vector illnesses, exacerbated by overcrowding in the area, a lack of health services, and poor water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) infrastructure.

“Accessibility to impacted communities and an uninterrupted supply of essential health and nutrition commodities are our key issues at this stage, if widespread famine is to be prevented and lives saved,” says Dr. Khan.

“One thing we know about famine is that it will spread if it doesn’t receive the necessary response needed from across the international community. Otherwise, it is going to spread like wildfire.”

The crisis in Sudan: Concern’s response

Concern has been in Sudan for nearly 40 years (including in West Darfur and South Kordofan), in that time reaching hundreds of thousands of people - all of whom are more than both the past and present conflicts affecting them.

While Concern’s team in Sudan have also faced challenges of safety and logistics, many of our team members have stayed on, responding to the needs of their compatriots. We have been able to respond to an ever-changing situation and ensure that help is going where it’s needed most. In the first nine months of the conflict (April - December 2023), we reached over 346,000 people with lifesaving support.

In addition to supporting 90 clinics in the country, Concern is also procuring and distributing food, including cereals, pulses, sorghum, dried vegetables, and cooking oil. We also provide emergency cash payments to those who have no source of income, and are working with families to build their resilience and generate income even in the most dire circumstances.

We are also responding to the influx of Sudanese refugees in neighbouring Chad (where we’ve worked for 17 years) and South Sudan (where we’ve worked for 13 years).