Read our 2023 annual report

Knowledge Hub

With hunger levels rising, can we still achieve zero hunger by 2030?

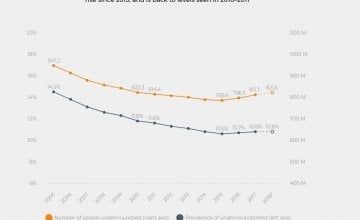

For decades, the number of hungry people in the world had been declining.

However, since 2015, this is no longer the case.

According to a new report launched by the United Nations yesterday, more than 820 million people do not have enough food to eat and as a result, go to bed hungry every night.

The two most recent editions of the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) report had already offered evidence that the decades-long decline in the prevalence of undernourishment in the world had ended and that hunger was slowly on the rise.

Speaking following the release of the report this week, our Head of Global Advocacy Réiseal Ní Chéilleachair highlighted the need for immediate action on the factors contributing to the increase.

The evidence is clear. Current policies, practices, and behaviours are exacerbating inequality, and worsening the lives of the poorest people. 820 million people go to bed hungry every night and something has to change.

A slow but steady increase

This year’s report confirms the total number of undernourished people has been slowly increasing for several years in a row and is now back to the same levels seen in 2010 – 2011. This means that over 820 million people suffer from hunger today, the equivalent of one in every nine people in the world.

Additionally, nearly 50 million children under the age of five are suffering from acute malnutrition. Globally, the prevalence of stunting (a lower than average height for a child’s age) among children under five years is decreasing and the number of stunted children has also declined, but 149 million children are still suffering from the condition, which can result in lifelong health problems.

For many children, undernutrition begins in the womb as mothers are not able to access the healthy diet that they need. The children who survive these risky pregnancies and the first critical months of life are more likely to have some form of malnutrition.

What is driving hunger?

Some of the key drivers of hunger and food insecurity include conflict, instability, and climate change. Conflict and instability have increased and become more intractable, spurring greater population displacement, which leads to a greater demand for food in places already suffering from food insecurity. Additionally, climate change and increasing climate variability and extremes are affecting agricultural productivity, food production and natural resources, with impacts on food systems and rural livelihoods, including a decline in the number of farmers.

Is achieving SDG Goal 2: Zero Hunger still possible?

In 2015, world leaders agreed to 17 Sustainable Development Goals for a better world by 2030. With these new results, it means achieving SDG Goal 2: Zero Hunger will be an immense challenge.

In order to meet the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, we must have a transformational vision which recognises that our world is changing and that brings with it new challenges. These challenges must be overcome if we are to live in a world without hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition in any of its forms.

Our actions to tackle these troubling trends and changes will have to be bolder, not only in scale but also in terms of multisector collaboration. This must involve agriculture, food, health, water, sanitation, education, and other relevant sectors in different policy domains. The health, education, agriculture, social protection, planning and economic policy sectors all have a role to play, as well as legislators and other political leaders.

At Concern, we are supporting communities with livelihood interventions including agriculture and graduation programmes. Our agriculture approach is Climate-Smart Agriculture (CSA), which promotes agriculture that sustainably increases productivity and resilience.

Some of the practices that we promote under CSA include the diversification of crop varieties, conservation agriculture, integrated pest management, post-harvest management, increasing access to improved farming skills and technologies, and strengthening links with the private sector to facilitate access to agricultural inputs from seeds to new equipment such as solar water pumps.

“Graduation” refers to the movement of individuals and households out of extreme poverty and into food security and sustainable livelihoods. Our graduation programmes are designed to create pathways out of poverty for the extreme poor by providing them with a comprehensive package of support (social assistance, livelihood development, and access to financial services).

As part of our nutrition programmes, we support national governments in strengthening their health systems to provide quality treatment for acute malnutrition using the CMAM approach. Where needed, we implement directly but also work through partner NGOs. We are also working on behaviour change towards improved IYCF (Infant and Young Child Feeding) and this often happens through women groups (care groups, mother-to-mother support groups). We're also working to make agriculture more nutrition-sensitive by ensuring that increased and diversified production is resulting in improved nutritional status of women and children.

Read the full State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World (SOFI) report

Please note, our 2019 Global Hunger Index will be released on October 15.