Read our 2023 annual report

Knowledge Hub

There’s no way around it: If we want to end poverty, we have to end hunger.

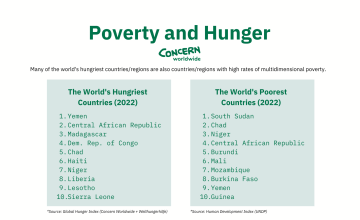

There is a strong regional overlap between the world’s hungriest countries and the world’s poorest countries. Malnutrition is highest among the poorest 20% of people in most countries, and when one rate is high in a county, it’s a sure bet that the other isn’t too far behind.

Somalia is one country that sits high on both lists. The country’s rural northern region is home to Nimco, a young mother of six children. The worst drought to hit the Horn of Africa in 40 years has turned the pastoralist landscape of Nimco’s village into a dust bowl. The soil is parched, and any remaining animals are thin and weak. All surface water sources have dried up. Since May of 2022, the community has been decimated: Those with the means left months ago

What causes world hunger?

Hunger is something we’ve all experienced for a variety of reasons. But when we break down hunger into issues like malnutrition, undernutrition, or specific deficiencies (like Vitamin A or Iron), we can more easily measure and design solutions to hunger that work.

That said, there are many causes of world hunger. To narrow things down a bit, we can put these causes into one of two larger categories: physiological causes and poverty-related causes.

Physiological causes of hunger

At certain points in our lives, we need more food and nutrients. The first 1,000 days of childhood are crucial for the right amount of nutrients to ensure that we continue developing to our full potential. When puberty hits and we reach adolescence, we go through another phase. For pregnant people, that need once again crops up.

While these life cycles aren’t “bad,” they are causes of hunger in that our nutritional needs increase in this time. Mothers like Nimco often face tough decisions during their pregnancies.

Poverty-related causes of hunger

That’s because of the millions of parents who face restricted resources and are unable to meet their most basic needs. Nimco, for instance, had relied on credit from local shops to feed her young family. As her debts accumulated, however, the shops stopped selling to her.

Both hunger and poverty can be intergenerational

Generally, stories like Nimco’s don’t happen out of thin air. The cycle of poverty often runs from one generation to the next, with children born into poverty more likely to live in the same cycle as their parents if there is no intervention. Likewise, hunger and malnutrition can be intergenerational.

Malnourished mothers are also more likely to give birth to malnourished infants. About 20% of stunting in children is attributed to malnutrition in the womb as a result of maternal undernutrition. This means even children who manage to survive being born to malnourished mothers are still less likely to reach their physical and cognitive potential in life.

Furthermore, many of the poverty-related causes of malnutrition, such as food insecurity or poor access to health services, endure for multiple generations of the same family or community.

Poverty and hunger in numbers

Global hunger

According to the World Food Programme, as many as 828 million people were affected by hunger in 2021 — a 22% increase from 2019 driven largely by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Stunting and wasting

In 2020, the World Health Organisation estimates that 149.2 million children under 5 — about 22% of the population — were stunted, and 45 million children suffered from wasting.

Child deaths

Approximately 45% of child deaths are linked to undernutrition. The majority occur in low- and middle-income countries.

Hunger and poverty

In most countries, malnutrition rates are highest among the poorest 20% of the population.

Diet and poverty

The WFP estimates that, in 2020, 3.1 billion people could not afford a healthy diet. This represents a 112 million-person increase from 2019.

Future projections

The WFP projects that, by 2030, nearly 670 million people (8% of the global population) will still be hungry, despite the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal of Zero Hunger by that year.

How does poverty affect hunger?

Issues relating to hunger can go hand-in-hand with poverty — particularly climate change, conflict, and forced migration. However, all of these situations usually boil down to three key issues. This is a framework Concern uses, one that was developed by UNICEF:

Poor or no access to a quality diet

In some cases, the question is simply whether people can find anything to eat. There is already an overlap of countries experiencing both high levels of poverty and hunger. The human cost of a food shortage will hit on this overlap, leaving those furthest behind with the fewest options in a situation of low supply and high demand.

In South Sudan, people fleeing war have described eating water lilies to survive. In Haiti, a common recipe in areas that face food shortages is bonbon tè, which are cookies made with a special dirt mixed with salt, fat, and water. Pastoralists in drought-struck northern Kenya boil animal hides.

However, even in less dire straits, people with the fewest resources are more likely to lose out on a well-balanced diet and key nutrients, relying on crops like corn for the majority of their diet.

Lack of knowledge, skills, and support to ensure optimal care for women and children

Education and poverty are also linked, especially when it comes to health and nutrition. The harmful patriarchal and gender norms present in many low-income countries (particularly in rural areas) mean that many women don’t realise the care they need to take while pregnant and nursing. Many parents also rely on traditional methods of treating their children when sick, many of which are ineffectual — and some of which can even be counterproductive.

Educating parents about proper prenatal and paediatric care (and giving them access to trained professionals, no matter how remote their community is) is a key aspect of ending hunger. When caregivers are informed about how to prevent, detect, and treat malnutrition, lives are saved. When expecting parents are aware of how nutrition is passed on to a child during pregnancy, they can take the care to get the nutrients they need in order to start their child off on the best possible foot.

Poor or no access to water, sanitation, and essential health services

Water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) as well as other key health services are also linked to poverty and hunger. Sometimes, people (especially children) eat enough. But if they live in an area with insufficient sanitation or poor hygiene practices, they may be susceptible to diarrhoea or other waterborne illnesses that prevent them from absorbing those nutrients. Making sure that drinking and washing water are uncontaminated can save a life — in more ways than one.

Likewise, essential healthcare services are, well, essential to ending hunger. This is especially true for women and children, who often don’t get adequate care or nutritional screenings at key moments in life.

Drought is also a key issue. “Before the drought, we had 40 sheep and goats. We depended on our livestock as we used to sell milk, meat, sheep, or goats,” Nimco explains. She lost all but 11 of her flock. “This is not the first drought,” she adds. “The drought has been here for the last two and a half years. Now we do not have anything to trade or anywhere to go. We are trapped in this tiny village.”

Why (and how) Concern tackles both poverty and hunger

Concern’s mandate is to end extreme poverty (whatever it takes). But we won’t end poverty until we also end hunger. If poverty is a combination between inequality and risk, then hunger creates vulnerability. This in turn feeds into the risks that fuel poverty. Food insecurity itself can also be an inequality within a community, or simply signal the other inequalities within that community.

Human development is not possible without good nutrition — particularly for women and young children. Stark evidence now demonstrates the enormous scale of nutritional issues in low-income countries, as well as their human and financial costs. As a result, Concern — like many other NGOs, as well as governments and UN agencies, has made unprecedented commitments to prioritise nutrition in our work around the globe.

Currently, our nutrition strategy is to focus efforts on reducing hunger and malnutrition among adolescent girls, women of reproductive age, and children under the age of 5. We work with adolescent girls to understand how to take care of themselves and advocate for their health and nutrition so that those who eventually become mothers bring a solid nutritional foundation to their pregnancies. We do the same with pregnant and lactating mothers, working with them to track and maintain their vitamin and nutrient levels. Some of our projects focus specifically on the first 1,000 days between conception and a child’s second birthday to prevent malnutrition in this critical time. Other programmes, like Community Management of Acute Malnutrition, screen and treat children up to the age of 5 (and even older) with overwhelmingly positive results and standard-setting cure rates.

A few other ways Concern approaches hunger in context of our work to end poverty include:

- Supporting nutrition-sensitive agriculture and crop diversity to ensure that families have the full range of nutrients they need

- Promote nutrition-sensitive social protection and natural resource management, placing nutrition and health at the forefront of responses to other emergencies such as climate change and conflict

- Working more largely towards gender equality and gender transformative programming

- Working more largely towards improving access to water and sanitation services, while also promoting optimal nutrition, health, and hygiene behaviours

- Increasing access to quality education, especially for girls

- Strengthening local and national health systems so that they can deliver integrated nutrition services (such as CMAM) without ongoing support from Concern

Back in rural Somalia, Nimco has found some relief from the poverty and hunger trap into which her family had fallen. Unconditional cash transfers from Concern have allowed her to buy food and water, and to pay off some of the debt that was weighing the family down.

It’s a short-term solution for sure, but it has slowed a spiral from which the family might never have recovered. Meanwhile, programmes that support alternative sources of food production and income generation are the bedrock upon which families like Nimco’s can build their resilience to poverty and climate shock. For Concern’s teams in countries like Somalia, it’s programmes like these that will ultimately help break the vicious cycle that ruins so many lives around the world.