Read our 2023 annual report

Knowledge Hub

The rapid development of COVID-19 vaccines has been extraordinary.

But the pandemic will only end when everyone across the globe is protected. Just over a year since the first vaccines were administered, that process is way off track. Here’s a look at what’s going wrong — and what can be done.

The problem

Now in its third year, the coronavirus pandemic has disrupted every society on earth and fundamentally changed how we live our everyday lives. Over 5.6 million people have died as of late January 2022, and the lives of billions more have been put under strain.

The successful development and rollout of several vaccines has given the world hope that it is possible to get the pandemic under control. A booster shot has also been developed to offset variants, and while its efficacy against Omicron is not as high, those who have been vaccinated and boosted, on average, have milder symptoms.

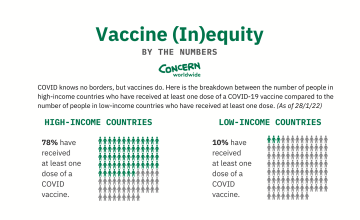

But while COVID knows no borders, the vaccines do. On average, 78% of the populations in high- and middle-income countries have received at least one dose of an approved vaccine as of January 28 2022. In low-income countries, just 10% have received at least one dose.

The toll of the pandemic beyond health

At Concern, we’ve seen first-hand the catastrophic impacts of COVID-19 in many of these low-income countries. In many of the countries where we work, there are impacts just as devastating than health. The economic toll of lockdowns has led to unemployment for millions, which in turn means people are unable to feed their families. While many high-income countries have provided social protection to those who have lost jobs, this type of assistance isn’t possible in many low-income countries. The result is a worrying increase in hunger and poverty.

Healthcare systems that were already weak simply don’t have the resources to deal with the virus, and a lack of access to clean water and soap is preventing efforts to curb the spread. "The biggest problem is oxygen supplies in a country with a health system that is already very fragile," says Concern country director Yousaf Jogezai of the situation in Malawi. "Hospitals in Malawi need sufficient supplies of oxygen to save lives, but it is extremely hard to get right now, with demand so high in many countries. Hospitals are also full, short staffed and in need of more equipment. People here are very worried."

The vaccine inequity gap

Throughout 2021, an income gap has widened with regards to vaccine equity. While vaccines have been distributed for free in countries like Ireland, each dose still has a price; between €2 and €35 according to UNICEF and the Gavi Vaccine Alliance. Distributing both doses of the vaccine incurs an additional estimated €3.30. This may not seem like much for a country like the Ireland: Data from the UN, World Health Organization, and UNICEF show that high-income countries only have to increase their healthcare spending by 0.8% to cover the cost of vaccinating 70% of their populations.

This isn’t the case in low-income countries, where the average annual spending on healthcare is €37 per person. As such, most countries would need to increase their healthcare spending by nearly 57% in order to vaccinate 70% of their populations.

To go back to Malawi, that would be akin to the country spending nearly 8% of its annual gross domestic product (GDP) on vaccinating a population of 19 million people. For Ireland, vaccinating a population of nearly 4.94 million costs 0.05% of its annual GDP.

Hospitals in Malawi need sufficient supplies of oxygen to save lives, but it is extremely hard to get right now, with demand so high in many countries. Hospitals are also full, short staffed and in need of more equipment. People here are very worried.

The cost of a free vaccine

Globally, distribution of the vaccines (and the science behind them) has been treated as the private property of pharmaceutical corporations. This is especially unethical as many of these vaccines were developed largely with public funding provided through a global effort. As of last November, the Pfizer company expected to earn about $81 billion in sales from the vaccine for 2021 (more than double their mid-year forecasts).

AstraZeneca has promised to provide the vaccine at a not-for-profit price “in perpetuity” for a list of low- and low-middle-income countries; however, at least 34 qualifying countries were discovered to be left off that list, including Angola, Timor-Leste, and Zimbabwe.

Moderna, which received $483 million from the US government to develop its vaccine, has by some advocacy group estimates seen a profit margin of 44% per dose, and has indicated that it would raise vaccine prices after the pandemic ends.

The solution: Vaccine equity

Even though COVID is around to stay thanks to its variants, equal access to the most effective COVID-19 vaccines is still critical. Vaccine equity would mean distributing these doses equally across all countries based on need first, regardless of the recipient’s nationality or wealth. Health workers, other essential frontline workers, and those most vulnerable or at risk of contracting the virus in every country must be prioritised.

Unfortunately, this didn't happen in 2021, and is unlikely to happen in 2022.

According to the Independent Panel on Pandemic Preparedness and Response, launched by WHO last summer, high-income countries have ordered twice as many doses as needed for their populations. An IPPPR report published in May recommended that high-income countries help to redistribute at least 1 billion doses of vaccines to 92 low- and middle-income countries by September 1, and a further 1 billion doses by mid-2022.

Now is the time to show solidarity with those who have not yet been able to vaccinate their frontline health workers and most vulnerable populations.

600 million doses were pledged as of the end of August 2021. As of autumn 2021, 92 countries classified as low- and middle-income received an estimated 89 million vaccines, well below the commitment made by countries and even further below the 1 billion minimum. Competition between high-income countries for access to vaccines is increasing political and diplomatic tensions, while depriving other countries access to limited stocks. At the current rate, global vaccination may be impossible before 2024.

What needs to change to reach vaccine equity?

1. We must agree that vaccines alone are not enough.

A vaccination programme alone cannot stem the pandemic. It is just one of a number of essential tools and approaches that all countries require to deal with the virus, its variants, and the multidimensional crisis left in its wake. The lessons learned in 2020 of how countries dealt with exposure and depended on their resilience must be used to respond to further waves of this pandemic and to prepare for the next global crisis. A global commitment to resilience will help build the foundation for stronger responses and quicker containment of similar crises in the future.

2. We must acknowledge that mutations could continue to reduce the efficacy of existing vaccines.

The race between high-income countries to buy up vaccinations is short-sighted, as we’ve already seen the virus is rapidly mutating in ways that reduce the efficacy of some vaccinations. Furthermore, the World Health Organisation has said that the proportion of the population that must be vaccinated to achieve herd immunity is likely to be higher than previously estimated. The longer the virus exists in a context of patchy immunity, the greater the chance of mutations, like Omicron, that could render the existing vaccines less effective or ineffective.

3. Governments: Stop prioritising vaccine patents over a culture of sharing and transparency.

We must do everything we can to share knowledge, scale up production, and reduce the cost of vaccines to ensure that the most vulnerable people in all countries get access to vaccines as soon as possible. Political pressure could help ensure that investments in vaccine development translate into patent waivers and prevent privatisation of profit from public money.

Governments must back South Africa and India's proposal to the World Trade Organisation Council to waive intellectual property rights for vaccines, treatments and tests until the world has reached critical herd immunity and the pandemic is under control — something which has already been done for HIV treatments.

4. Corporations: Share access to data and technology to save lives.

Similarly, initiatives like the World Health Organization’s COVID Technology Access Pool (C-TAP), where companies can share data and patents on their innovations, should be mandatory.

To date, not one company has joined C-TAP and AstraZeneca is the only company that has committed to selling the vaccine for no profit for the duration of the pandemic (and in perpetuity for a select list of low-income countries). As a result, much of the world’s vaccine production fell on a single company in India which was forced to halt exports during the surge of the Delta variant. Much of this could have been avoided with an intervention like C-TAP.

5. Individuals: Rally your TDs.

Contact your TDs and rally them to use their power to affect change. Vaccinating those on the frontline and the most vulnerable everywhere — irrespective of their wealth or nationality — is not a choice but a necessity. It is the only way back to something like 'normal.'