Read our 2023 annual report

Knowledge Hub

Over the last 80 years, NGOs have helped reduce global hunger and poverty rates by orders of magnitude. Yet both are once again on the rise. What happens next?

For nearly 60 years, Concern has been guided by a simple yet powerful mandate: “Do as much as you can, as well as you can, for as many as you can.”

Those words came from Fr. Aengus Finucane, one of hundreds of Irish Catholic priests who were working in Biafra, a region in eastern Nigeria that attempted to gain independence in 1967. What followed was a two-and-a-half year war that led to at least 2 million civilian deaths and a famine that broke out in 1968. Aengus watched as the members of his parish begged for help and buried their children. “As a young priest, I was not prepared to deal with this,” he later recalled. “It was unimaginable.”

Concern was born in 1968 as a response to that famine, with Aengus and his brother, Fr. Jack Finucane, working to distribute aid that was being rallied back home in Ireland by Concern founders John and Kay O’Loughlin-Kennedy (who had become aware of the famine via John’s brother and fellow priest, Fr. Raymond Kennedy).

Signs of the times

Concern’s beginnings came at a time when humanitarian aid and development were changing in the wake of World War II, in an effort to support international development and prosperity. Part of this came with rebuilding Europe after two world wars to ensure stable growth and recovery without the risk of a third war.

Aid had existed before then — Ireland was on the receiving end of it during the Irish Famine, including from the Choctaw Nation, who themselves were impoverished but nevertheless donated $5,000 in today’s currency to support people 7,000 kilometres away. A 1984 editorial in the Irish Press, responding to the famine that was then gripping Ethiopia, urged readers to “act in the name of Christian charity and of common humanity as a country that has itself known the horror of famine.”

Twenty years earlier, however, there was another connection between Irish history and its NGOs: In the early 1960s, many countries across Africa began to gain independence from former colonising countries in western Europe. Similar shifts began to happen in southeast Asia, with many countries facing shaky futures as they gained their own footing.

“Activity in the field of aid and development was often presented as part of a longer narrative that linked work in […] independent Africa and Asia with Ireland’s own experience of state-building in the Twentieth Century,” writes Kevin O’Sullivan in the journal Irish Historical Studies.

“The caring nation”

O’Sullivan’s article is titled “The Caring Nation,” based on an exchange between an NGO leader and an Arab doctor leaving Somalia’s Baidoa refugee camp in 1992. When the doctor learned that the NGO leader was from Ireland, he sighed: “The caring nation.”

That identity has formed the backbone of Irish aid. Concern’s founding in 1968 predated the establishment of Irish Aid, the national government aid programme, by six years. The Irish Government had made contributions to multilateral partners since gaining independence and, more significantly, after joining the United Nations in 1955, while continuing to receive assistance from the European Union to improve infrastructure and living standards. (Irish Aid estimates that the country received over €40 billion in EU funds between 1973 and 2018.)

Despite no shortage of things that needed to be taken care of at home, however, Ireland has remained committed to doing as much as it can, as well as it can, for as many as it can — particularly through its NGOs.

Sending (more than) one ship

Concern began as SOS — “Send One Ship” — with the idea of (you guessed it) sending a single ship with famine relief to Biafra. However, it didn’t stop there. Soon after our Biafra response, we began to work in a newly-independent Bangladesh and, one year later, Ethiopia. With each response, we brought on more technical experts and national staff who knew the specific needs of the communities where they grew up.

This was combined with the tireless advocacy done by many of our leaders over time. One key moment during the 1984 famine in Ethiopia, known now as “the first televised famine.” Jack Finucane was a key figure in helping to bring media attention to this crisis; coverage that launched an unprecedented international response.

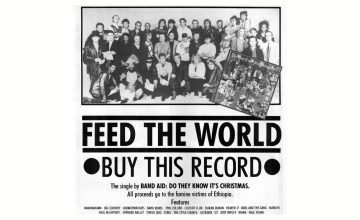

While managing a team of nearly 950 on the ground (93% of whom were Ethiopian nationals), Jack brought a young Irish singer named Bono to the country for the first time, and also consulted with Bob Geldof, whose fundraising concert Live Aid raised €160 million for famine relief. You may never be able to get the song “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” out of your head, but it was a major moment in showing what collective star power could do to bring attention to the right cause.

In the numbers

Since the middle of the last century, NGOs like Concern have played a key part in reducing poverty and hunger rates — as well as several other key indicators linked to both issues (that also sit at the heart of the Sustainable Development Goals). Looking at the specific challenges faced by specific communities has helped us come up with better (and often more cost-effective) solutions.

We have found better ways of addressing hunger crises (including famines) with therapeutic food and community-based care for acute malnutrition. But we’ve also focused on development — the longer-term planning to prevent these crises from happening in the first place. The Food and Agriculture Organisation notes that increased investment in agricultural support in the 1970s and 1980s had an enormous impact on improving both nutrition and incomes for families.

The impact that organisations like Concern have had is in the numbers: In the 2025 Global Hunger Index (co-published by Concern and Welthungerhilfe), Alex de Waal noted that, between 1870 and 1970, approximately 1.4 million people died each year from “epidemics of starvation.”

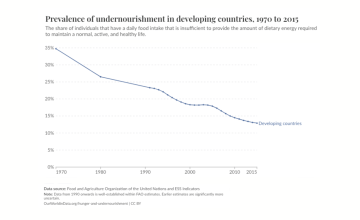

By contrast, between 2000 and 2015, roughly 40,000 people died each year from hunger- and malnutrition-related issues. Data compiled from the FAO and UN show that, in 1970, nearly 35% of people living in low-income countries were malnourished. A decade later, that figure dropped by over 10 percentage points (26.5%). By the time the 2015 GHI was published, we were at an all-time low of 12.9%.

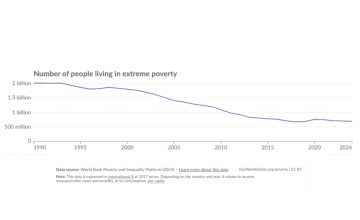

Likewise, the World Bank estimates that, in 1950, the global extreme poverty rate was at 58.5%. Up until 1990, those rates declined by approximately half a percentage point each year, with that reduction rate doubling in the final decade of the last century.

In round numbers over the last 35 years, we went from 2 billion people living below the poverty line in 1990 to an all-time low of just over 667 million in 2018.

1.3 billion steps forward, 8 million steps back

However, NGOs can’t account for everything. In 2024, the global poverty rate was at just under 692 million. It was even higher in previous years.

Similarly, while undernourishment rates in low-income countries were at 12.9% in 2015, they began to increase in 2018 amid a worsening climate crisis and rise in global conflict. The COVID-19 pandemic, which severely set back poverty reduction, also increased global hunger rates. Approximately 2.4 billion people in 2022 faced moderate or severe food insecurity, up from 1.75 billion in 2015. Globally, the FAO estimates that we lost nearly 15 year’s worth of progress in eliminating undernutrition between 2018 and 2022:

So, does that mean NGOs failed?

Not exactly. Let’s look at the three major contributors to the rise in poverty and hunger rates today. As we’ve said since 2020, the net effects of COVID-19-related lockdowns are still being felt today. The World Bank notes that, between 2020 and 2023, the pandemic led to an additional 70 million people living in extreme poverty, and more than $10 trillion in estimated economic losses. On its own, this impact, while severe, may have been manageable.

However, these losses came on top of two protracted crises: climate change and a rise in conflict. Many of the countries hit hardest by climate disasters in recent years have also been low-income countries whose residents primarily rely on agriculture for both their livelihoods and their food security. Additionally, conflicts have increased by 65% in the last three years, with 56 recorded during 2024 — the most since World War II. Many of these conflicts are protracted, leading to years (and in some cases decades and even generations) of displacement, and many of them are also happening in the same countries facing the effects of climate change and the pandemic.

While there are organisations that do more harm than good, the sector overall has helped with many of the advancements we’ve achieved in the last half century and are powerful allies for civilians against forces beyond their control (like pandemics, natural disasters, and conflicts). The longer a country is locked in conflict, the more fragile infrastructure and social systems become, and that’s where we can help fill in the gaps while leaders work towards political solutions. We shouldn’t replace these services long-term, but the sooner we are able to respond, the more we can offset against greater losses.

Why we’re needed now more than ever

The good news is that support for humanitarian and development aid remains high in Ireland. According to Dóchas, the Irish network for international development and humanitarian organisations, 76% of the country agrees that it is important to provide overseas aid. 57% of people consider it a moral obligation, and 29% are even in favour of increasing the level of spending.

76% of Irish agree that it is important to provide overseas aid, 57% consider it a moral obligation, and 29% are even in favour of increasing the level of spending

In some cases Concern has remained active in countries like Bangladesh and Ethiopia for decades. However, our real aim is to work ourselves out of a job. We hope to do so in both of these countries, but the reality of our world is that some contexts take more time than others.

For a success story, however, we can look to our work in Cambodia, which began in response to the Khmer Rouge genocide and civil war within the country (1975-79). While the war came to an “official” end in 1979, violence continued well into the 1980s. It wasn’t until 1991, with the signing of the Paris Peace Accords, that hundreds of thousands of Cambodians were able to return home.

This can also be a delicate moment in establishing peace, as resources are depleted during a war and can create tensions among those who return and those who never left. However, Concern was prepared for this. One of our initiatives to facilitate sustainable recovery was a savings and loan initiative. We began in 1998 with a small, five-person microfinance team that supported farmers, merchants, seamstresses, and chefs.

By 2002, that five-person team became its own microfinance company, known as AMK. The following year, Concern transferred AMK to Cambodian ownership. Between 2007 and 2014, Cambodia’s poverty rate fell at a miraculous pace: from 47.8% to 13.5%. In 2013, Concern handed over operations to local organisations. We had reached our main goal: We were no longer needed.

While no NGO is perfect, at our best this is the work we are able to achieve: serving as support when one or several systems aren’t able to keep up with the demand brought on by one or more overlapping crises. On top of that, we refine our work every day in order to increase our reach and effectiveness. We do as much as we can, as best as we can, for as many as we can. And we’re ready to do more.