Read our 2023 annual report

Knowledge Hub

Like many emergencies, the climate crisis isn’t gender-neutral or a great equaliser.

“Climate change is creating a downward spiral for women and girls,” said UN Women’s Deputy Executive Director Sarah Hendriks last year at COP 28. As a result, the UN estimates that, by 2050, climate change will push as many as 158 million more women and girls into poverty and leave 236 million more women experiencing hunger.

This is the result of a disastrous combination: Women and girls are statistically more likely to live in extreme poverty, and the climate crisis has a disproportionate effect on low- and lower-middle-income countries. But what does that actually mean? What does it look like for the women and girls most affected by the climate crisis, and why are they being left furthest behind? Here are five things you need to know about women and climate change.

1. Women are largely responsible for natural resources, but don’t enjoy equitable access to them

As our activist friend Bono put it at a Concern event: “Women can work the land, but they can’t [expletive] OWN the land.” Per the Food and Agriculture Organisation, women make up 43% of the world’s agricultural workforce, yet fewer than 15% of the world’s landholders are women. Even if it’s a family plot that’s passed down from one generation to the next, in many countries it’s still illegal for women to own property.

This puts women at a significant financial disadvantage for being as successful as their male counterparts, especially in many of the countries most affected by climate change, where farmers face greater pressure to adapt to changing environmental norms. Moreover, nearly half of all women in agriculture (49%) work as contributing family workers, meaning that they receive little to no pay. Only 10% of men work under these conditions.

Land is just one of the natural resources women are responsible for, but often lack equity in accessing. Women and girls are often the ones who collect water for their families. As this resource becomes more scarce, this task becomes more time-consuming; UNICEF estimates that women and girls spend a total of 200 million hours fetching water each day, calling this “a colossal waste of time". Likewise, collecting food and firewood as well as other natural fuels are often chores left for women and girls, trips that can leave them vulnerable to attacks, injury, and even death.

2. Women are less likely to survive a natural disaster

Speaking of risk, one report from the London School of Economics surveyed 141 natural disasters and came to the conclusion that female mortality rates are higher than men’s in situations where gender inequality is the norm. When women lack basic skills, such as literacy, swimming, or climbing trees, they have fewer ways to prepare for and cope with natural disasters. The UN Environment Programme points out that, in some circumstances, women and girls may not even be allowed to evacuate their home without a man’s consent.

3. Women who do survive a natural disaster have a harder time recovering

Those who do survive a flood, mudslide, drought, or earthquake are still vulnerable. In the wake of a climate-related emergency, people in affected areas often have to relocate — either temporarily or for a longer period of time. Female climate refugees are more vulnerable to sexual abuse and human trafficking in certain contexts. They also face greater discrimination when it comes to getting emergency supplies and humanitarian aid.

As UN Women notes, this creates a “cycle of vulnerability” against future disasters. With the climate crisis leading to an increased frequency and impact of natural disasters, this has harrowing prospects for the future.

4. Climate-related health issues pose a greater risk to women

There are a number of health issues that can be attributed (at least in part) to climate change. Air pollution leads to greater chances of respiratory disease like asthma, as well as cardiovascular issues. Floods, monsoons, and cyclones contribute to higher rates of waterborne illnesses. Food shortages driven by natural disasters lead to rising malnutrition rates.

This isn’t a shared burden. Women are often more susceptible to these issues. They inhale more toxins while cooking over unsafe stoves. They use more water in their daily routines, meaning they’re more susceptible to parasites and waterborne illnesses. Maternal and child health is often compromised by climate disasters, either in terms of access or in terms of maternity resources being diverted towards emergency response. Women are also the first to cut back on their food intake when harvests fail or run out.

They don’t suffer alone, either. Expecting mothers may pass on the effects of malnutrition or a disease like Zika virus to their unborn children, setting up another generation with personal setbacks linked to climate change.

5. Women are often ignored when designing solutions to climate change

A 2023 UN Women report revealed two damning statistics: Only 55 national climate action plans make a specific reference to gender equality, and only 23 of those plans recognise women as agents of change in addressing the climate crisis.

This exclusion is all the more true for Indigenous women, women who are HIV-positive, LGBTQIA+ women, women of a non-dominant race, caste, or ethnicity, and women whose other identities can leave them further marginalised beyond their gender. As the Thai activist Matcha Phorn-In put it: “If you are invisible in everyday life, your needs will not be thought of, let alone addressed, in a crisis situation.”

That said, women are key partners and leaders in the fight against climate change. Bringing their expertise and experience to the decision-making table will ensure that the ways we fight the climate crisis will be more sustainable, successful, and equitable — for all.

Women and climate change: Concern’s response

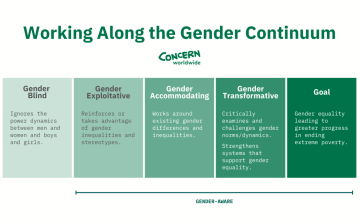

Concern’s climate change response is built on the understanding that we will only be able to curb the effects of climate change by addressing the challenges through a gender-transformative framework.

In northern Afghanistan, we lead a consortium working to contribute to the economic empowerment of women while responding to the changing agricultural needs of the region (which has been severely impacted by climate change). Last year, we successfully reached over 3,500 women and established 237 female-led agrobusiness collectives.

In the Bangladeshi cities of Dhaka and Chattogram, we’ve helped to establish 87 support groups for mothers. Working with community volunteers and nutrition hubs, the members of these groups were able to gain access to clean water — which is not always available to them. As a result, year-round access to safe drinking water stood at 84% in these communities.

From start to finish, our projects fully involve communities in the planning and execution process. We also make a point of finding the most vulnerable groups within each community — such as women and the disabled — to ensure that the solutions designed leave no one behind, whether they address the everyday effects of climate change or large-scale disasters.